November 8, 2018

This article will be featured along with other articles addressing investment opportunities in European agriculture in Volume 5, Issue 4 of the GAI Gazette, which will be distributed in conjunction with Global AgInvesting Europe 2018, held in London on 4-5 December 2018. Join us in London to hear valuable insight and best practices for investment strategy from the expert speaking faculty. Learn more and register.

By Micheal DeSa, AGD Consulting

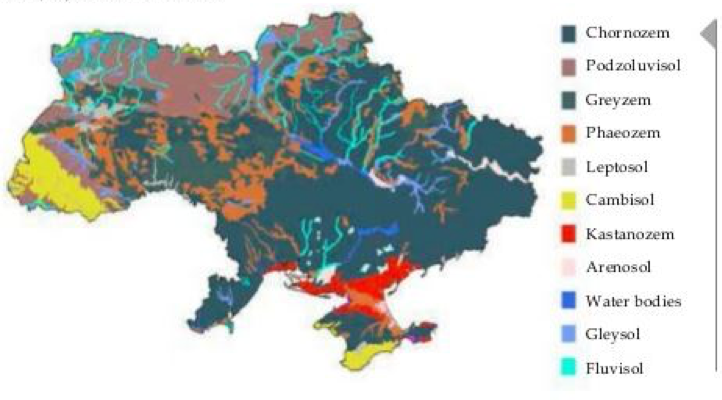

Ukraine’s agricultural production capability is often overshadowed by the country’s civil conflict and lack of business transparency. However, a closer look at this strategically-positioned agricultural powerhouse reveals there is ample opportunity for growth to meet the world’s increasing food requirements. Ukraine is the number two global leader in overall grain exports after the United States and takes the number three seat in corn exports.1 They are the number one producer of sunflower seeds and exporter of sunflower oil, reaching 1.16 billion tons of sunflower seeds produced in 2016/2017.2 Over 70 percent of the country’s total area is agricultural farmland, totaling more than 30 million hectares suitable for agricultural production.3 This level of production is accomplished on less than 10 percent of the total agricultural farmland in the United States, due in large part to the quality of soil. Ukraine boasts one of the richest concentrations of fertile soil on the planet, with over 30 percent of the world’s reserves of chornozem or “black earth” lying within its borders. The soil contains approximately seven to 15 percent organic matter necessary for quality crop production compared to two to eight percent in other parts of the world.4

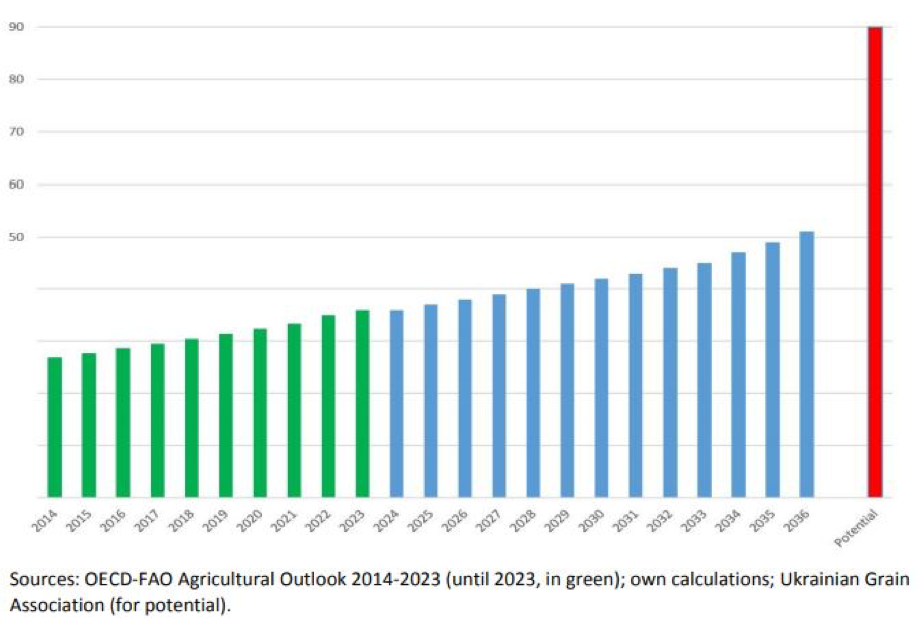

Even with quality soils and ample arable land, Ukraine is not producing anywhere near its potential. According to Ukraine’s Deputy Minister of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine for European Integration, Olga Trofimtseva, the country harvested 66 million metric tons of grain in 2016 and 62 million in 2017.5 She believes this is far from the limit, commenting that Ukraine could easily harvest 100 million metric tons in the coming years, subject to the development and use of new technology and land reforms. She isn’t the only one who believes Ukraine is operating at a production deficit. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development-Food and Agriculture Organization’s Agricultural Outlook for Ukraine projects Ukraine’s grain export potential could reach 90 million metric tons. Note that when the below graph was produced in 2014, Ukraine had already exceeded grain export projections for 2017 by nearly 20 million metric tons.

Ukraine Grain Export Growth Forecast (Million tons, 2014 – 2036)

If Ukraine could reach these production levels, this would give them an exportable surplus of approximately 50-60 million metric tons, assuming 40-50 million for domestic consumptions.6 An exportable surplus is an indication of country’s ability to supply a lower cost product to the global market, thereby increasing their competitive advantage.

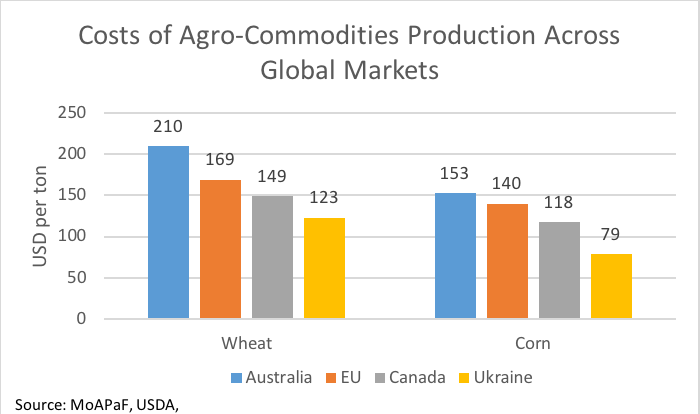

The ability of growers to keep production costs low can have a significant impact on profitability and growth potential. A direct comparison of farmland prices in the Ukraine to other markets on a cost per hectare basis is inconclusive due to wide variations in farmland productivity and land prices, therefore, land cost per unit of production is a more meaningful comparison metric. The utilization of a production-based benchmark allows investors to compare land values using different production characteristics. The graph below shows costs of production for wheat and corn in the Ukraine compared to several other markets.

Investing in farmland with low land costs per unit of production can allow an investor to realize greater capital gains through the application of things like new technology and modernized equipment, experienced management teams, and to the extent possible in the Ukraine, economies of scale. It is important to note, however, that this metric does not take into account the logistical costs/considerations of getting the commodity from the farm gate to the marketplace.

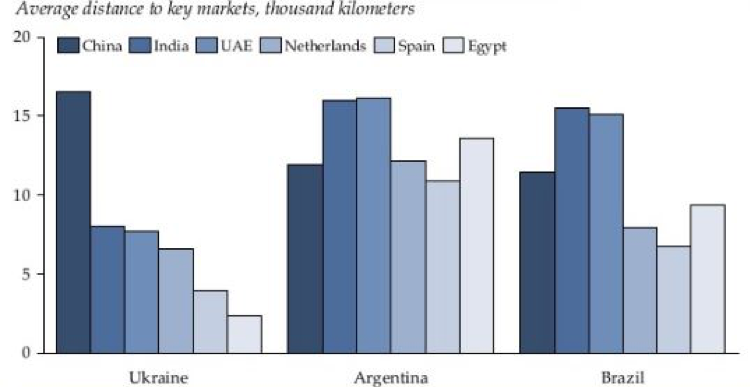

Ukraine’s geographic positioning to key European and Asian markets also provides additional cost-saving advantages. The graph below shows Ukraine’s advantageous positioning to key export markets.

Proximity to these markets helps keep transportation costs low and also provides steady demand for commodities as middle classes in places like the EU and China continue to grow. Finally, a large labor pool – 25 percent of the Ukrainian population is employed in the agricultural sector7 – providing another supporting parameter for low-cost crop production.

High quality, naturally occurring soil – low-cost per unit of production as a result of strategic positioning to key markets and a large labor pool – are all positive indicators of Ukraine’s agricultural investment potential. The caveat is that, because of the severe limitations to land ownership by foreign investors in the Ukraine, investors should examine opportunities outside direct farmland investments that still capitalize on the land’s productivity potential.

OPPORTUNITIES

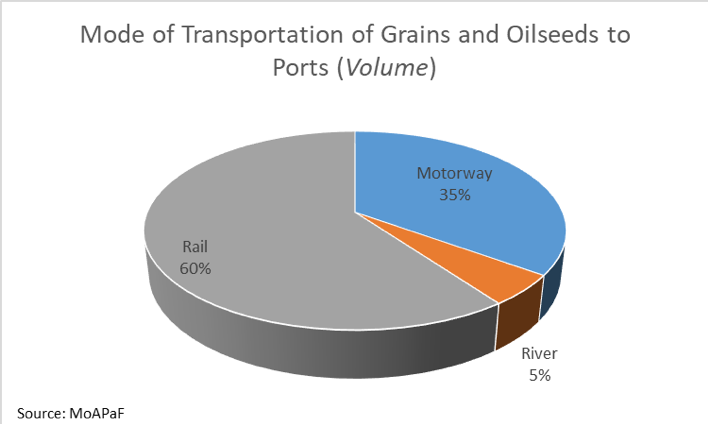

As grain production forecasts predict a sizable increase in output from Ukraine, investments will need to be made into the country’s transportation and storage infrastructure to support this increased supply. Logistic costs for moving grain from Ukrainian farms to the Black Sea ports are still approximately 40 percent higher than cost for comparable services in France and Germany, and 30 percent higher than costs in the United States.8 These high costs are often the result of poor logistics, specifically outdated railway transportation equipment, underutilization of river transport, and insufficient storage capacity leading to higher spoilage. As a result, farmers receive lower shares of the market prices and shoulder these logistical costs from their own balance sheets. These losses in annual revenue potential can range between US$600 million to US$1.6 billion.9

Catching the Train

A review of the Ukraine railway system reveals that currently 60 percent of grain volume in the Ukraine is transported via rail. The country boasts the 13th largest railway network in the world and can easily absorb the increased production forecasts with proper infrastructure development and equipment improvements.

For example, current rolling stock of Ukrzaliznytsia (UZ), the state-owned Ukrainian monopoly that controls the vast majority of railroad transportation in the country, is outdated and ill-equipped. A recent World Bank study estimated that a US$64 million investment in Ukraine’s railway infrastructure, including 8,500 grain hoppers, new wagons, and locomotives, could yield an Estimated Rate of Return (ERR) of 21 percent.10

While transportation from storage to port is primarily done by rail in the Ukraine, significant investment is also needed to improve river and barge infrastructure and deep water port facilities. Only five percent of exported grain is moved along Ukrainian rivers, representing a formidably untapped opportunity to transport bulk ag products reliably, efficiently, and at a low cost, especially along the Dnipro River. River transportation in the Ukraine is often less expensive and more environmentally efficient than railway transport, with unitary transportation costs of three to 8.9 USD per ton compared to 10.5 for rail and 16.4 for road.11 The same World Bank study estimated a US$580 million investment could yield a 21 percent ERR. This would include dredging the Dnipro River’s shallow bottom to accommodate larger ships and prevent freezing during peak production winter months, lock passages, bridges, and port storage infrastructure. This type of investment could also lead to a capacity increase of five to six million tons of grain annually by 2022 and a 30 percent reduction in costs associated with road damages by 2022.

Improvement to rail and river transportation infrastructure will allow Ukrainian producers to offer even lower cost per unit of production to offtakers, but grain storage is yet another key component of the value chain suitable for foreign investment. Sufficient and quality grain storage infrastructure will help Ukrainian farmers minimize loss and store grain longer. In 2014, Ukraine had a grain harvest of nearly 64 million metric tons, however, existing certified storage infrastructure allowed for immediate storage of only 45 to 65 percent.12 Many existing facilities are more than 50 years old while the complementary infrastructure supporting drying, loading/unloading, and testing operations are energy-intensive and employ little to no recent improvement from precision technology.13 According to the World Bank, a US$1.5 billion investment into 6.4 million metric tons of new elevator capacity could reduce grain loss by 15 percent per annum yield and return early investors a 24 percent ERR. Without appropriate investment, poor logistics will become a bottleneck to sector development rather than a vehicle of trade facilitation.

A Fluid Investment

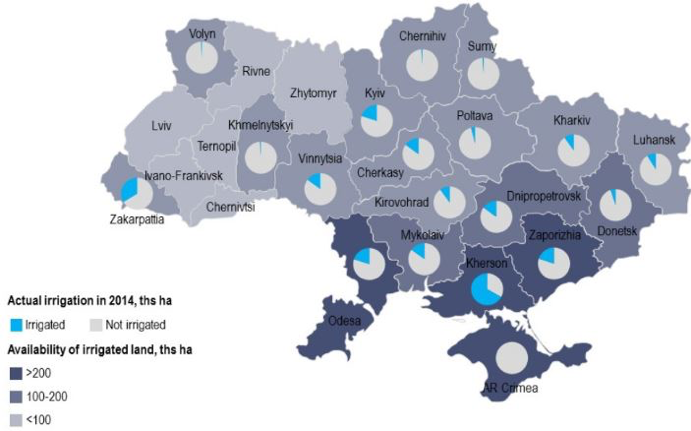

Opportunities exist in the upstream portion of the Ukrainian ag value chain as well, particularly in irrigation infrastructure. During the Soviet era, irrigation was widely used throughout the country. At one point, irrigation infrastructure grew by 100,000 hectares per year.14 While much of this machinery is now dated, proper maintenance and repurposing on the back of investment dollars could revitalize millions of hectares of existing infrastructure. At present, most Ukrainian farmers use dryland farming practices which place significant risk at the mercy of Mother Nature.

Irrigated land has the potential to produce two to two-and-a-half times the yield compared to traditional dryland farming, without the risk of uncertain precipitation conditions. A recent State of Nebraska irrigation study showed a yield of 4.7 million tons per acre of corn on irrigated land compared to a yield of 1.8 million tons per acre on dryland, resulting in a revenue growth of over $240 more per irrigated acre. Under the right structure and management team, this could be a profitable way to participate in the forecasted Ukrainian agricultural uplift.

Adding Value with Agtech

Finally, the application of precision technology to Ukraine’s agricultural sector will further allow producers to increase yield, reduce production costs, and optimize input consumption without the necessity for scale. There should be no doubt now that agtech is a booming sector across the globe. According to an August 2018 market intelligence report released by BIS Research, the global precision agriculture market is expected to raise US$10.55 billion by 2025, increasing at a CAGR of 13.7 percent from 2018 to 2025.15 With only three to four percent of arable land in the Ukraine under precision management, there is much room for growth.16 Early movers to this space who identify ways to apply precision technology to Ukrainian farm operations, while limiting their exposure to country risk, stand to do well.

One such area is soil erosion. According to the World Bank, Ukraine loses about 50,000 hectares of farmland every year from soil erosion and land degradation.17 Groups like AgriEye, a Ukrainian company founded in 2016, hope to cut this loss in half through the application of drone imagery, multispectral remote sensing, and open source geospatial imaging data. AgriEye uses this input data to create a precise field map of soil composition, which it then pairs with algorithms to analyze yield and provide prescriptive recommendations on how to irrigate and fertilize. While they charge for this service internationally, it’s free to Ukrainian farmers. Other Ukrainian firms like SmartFarming are applying data-driven solutions to help Ukrainian farmers reduce costs by as much as US$3,000 per hectare and save their producers more than 10 percent of inventories in a season through the re-equipment of machinery.18 Associations and accelerators like AgTech Ukraine, while only a few years old, are beginning to draw attention to the importance of technology in the sector.

RISK FACTORS

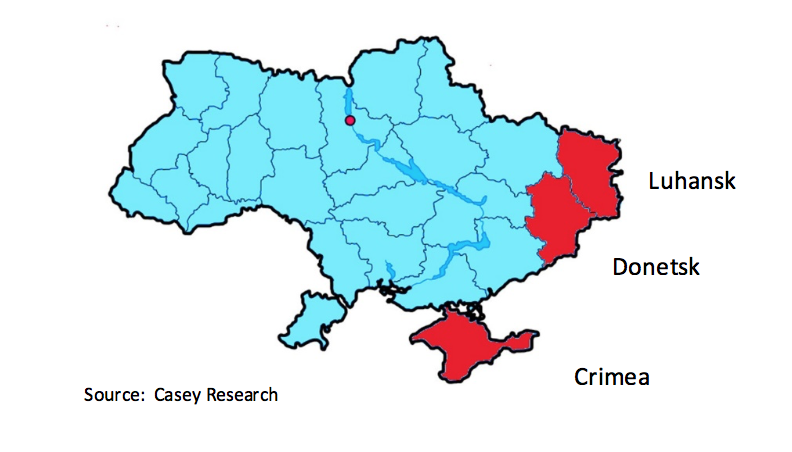

In spite of these opportunities, Ukraine is not a simple place to invest. Perhaps the most obvious challenge is the civil conflict, centered in the eastern provinces and Crimea. Notable conflict began in 2014 when then President Viktor Yanukovych, a pro-Russian supporter, refused to sign an association agreement with the European Union (EU). Opposition groups to the president, called Euromaidans, supported closer relations with the EU and ousted Yanukovych through a series of violent protests. Russia used this as justification to annex Crimea. The local Ukrainian government in Crimea, along with Donetsk and Luhansk provinces, was expunged and while the conflict has since quieted, it is far from over.

This unrest is affecting Ukrainian farmers on many different fronts. First, the majority of provinces under Ukrainian government control have lost access to Crimea and several eastern provinces and vice versa. If you’ll recall from the soil map earlier, these eastern and southern provinces were among the richest in “black earth” soil and therefore, some of the most productive. Secondly, as a result of the conflict, farmers in these affected regions have not only lost access to the Ukrainian domestic market, but also internationally, and are finding it increasingly difficult to access inputs like fertilizer and seeds. Before the conflict, Russia was a primary importer of Ukrainian commodities, especially from the eastern regions. Now, trade between these regions has all but ceased, putting further stress on Ukrainian producers. Finally, according to Raimund Jehle, FAO’s regional coordinator for Europe, many producers in these highly-fertile regions have turned to household production instead to survive the turmoil, and have given up attempting to sell their products domestically or abroad.19 Investors in Ukraine’s agricultural sector need to carefully examine how their capital may be affected by the ongoing civil conflict before deployment.

The land moratorium currently in place, which dates back to the transition from communism to capitalism, is another barrier to entry. When the Soviet policy of collectivism in Ukraine failed in the late 1920s due to drought and snow levels that resulted in the death of more than six million Ukrainians, ancestors of the victims were awarded small parcels of land averaging four acres each. Then in 2001, Ukraine’s government passed a law prohibiting the sale or purchase of these plots, a moratorium that is still in effect today over 25 years later and has been extended nine times already.20 Productivity in these 27 million hectares of distributed land is severely lagging as there is no incentive for local producers to improve land quality because they don’t actually own the land. The moratorium also prevents them from making any change to the land’s designating purpose, so transformation to a higher-value crop in the absence of selling it is also not an option. Farmers are permitted to lease their land for as long as 49 years, but since all adjacent landowners would also have to agree to lease in order to achieve any semblance of scale, this is not a viable opportunity. Supporters of the ban argue that without it, foreign companies from the EU or the United States would flood into the region, stripping this land away from generations of Ukrainian farmers for pennies and providing it to land developers. Calls for reform are getting louder as Ukraine’s agricultural productivity continues to lag its neighboring countries.21 Many institutional investors will continue to watch these policies closely, but until they change for the better will likely keep their capital on the sidelines.

Finally, a lack of transparency coupled with a tendency by the government to emphasis short-term solutions rather than pursue long-term fixes are additional risk factors to be considered. According to the 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index compiled by Transparency International, Ukraine ranked 130 out of 180 countries, placing it in the bottom third of all countries evaluated. While they took their first steps to fight corporate secrecy back in 2017 when they agreed to share data on who ultimately controls Ukrainian companies, past events such as former President Yanukovych’s ability to syphon off at least US$350 million of Ukrainian public funds for his personal benefit, will be challenging to overlook going forward.22 Even Ukraine’s own Deputy Minister of Agrarian Policy Olga Trofimtseva admits that the decision to cancel refunds on export VAT for soybeans and rape seeds was based on an “ad hoc policy, when a policy is not based on some strategy or long-term vision, but a short-term reaction to changes.”23 Yet another indicator of the government’s struggles to deal with systemic issues is the fact that in the Ukrainian agricultural economy, the investment burden is carried primarily by producers financing production from their own revenues. A study conducted by UkrAgroConsult in 2017 showed that the share of agricultural producers’ own money in total investment volume reached 70 percent in 2016,24 indicating that this method of self-financing from producers’ own profits is nearly exhausted. For comparison, the next highest source of capital investment came from bank credit and local budgets at only 7.1 percent of total volume.

Continued civil conflict in some of Ukraine’s most fertile regions, the 20-year-old-plus land moratorium, and a lack of transparency and financing opportunities for producers will continue to plague Ukraine agricultural producers as they search for alternate sources of investment capital.

FUTURE OUTLOOK

Ukraine’s growth potential as a low-cost, strategically-positioned grain producer is an opportunity that must be approached cautiously and with the right structure. Direct farmland ownership, at this stage, is not an option; and while long-term land leasing is possible, it exposes investors unnecessarily to naked commodity and legislative risks. While an increasing number of experts believe that opening up Ukraine’s land market to foreign investors will not only solve the problem of limited access to financing but also provide incentive for foreign capital to come in, it is not likely to happen in the foreseeable future. Therefore, investors seeking to capitalize on Ukraine’s projected growth in grain production should seek debt-based investments into parts of the ag value chain like transportation/storage infrastructure, irrigation, and precision technology applications. Finding and building a relationship with trusted partners who have boots-on-the-ground experience and a proven track record are essential for success. It also may be prudent to consider co-investments with groups like the World Bank or other NGOs as a way to bolster credibility and further protect an investor’s assets. While fortune does favor the bold, in Ukraine, those first steps must be calculated and protected, if one chooses to step at all.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael DeSa is the founder/managing director of AGD Consulting, a U.S.-based, strategic advisory and business development firm servicing the agricultural and resource sectors in emerging and OECD markets. His agricultural engineering background, 10- years of leadership and project management experience with the U.S. Marine Corps, and extensive travels and investment experience in emerging market countries make him uniquely qualified to counsel companies and investors throughout the region. Services include farmland and agribusiness due diligence, project origination, market assessment, and competitive analysis for precision ag technology and international project management. DeSa can be reached at michael@desaconsultingllc.com.

Michael DeSa is the founder/managing director of AGD Consulting, a U.S.-based, strategic advisory and business development firm servicing the agricultural and resource sectors in emerging and OECD markets. His agricultural engineering background, 10- years of leadership and project management experience with the U.S. Marine Corps, and extensive travels and investment experience in emerging market countries make him uniquely qualified to counsel companies and investors throughout the region. Services include farmland and agribusiness due diligence, project origination, market assessment, and competitive analysis for precision ag technology and international project management. DeSa can be reached at michael@desaconsultingllc.com.

# # #

DISCLAIMER: All views, data, opinions and declarations expressed are solely those of the author(s) and not of Global AgInvesting, GAI News, GAI Gazette, or parent company HighQuest Group.

1. Ministry of Economic Development and Trade of Ukraine. (2014). INVEST Ukraine Open for U. Retrieved from https://mfa.gov.ua/mediafiles/sites/rei/files/MEDT_Brochure_A4_View.pdf, pg. 6↩

2. Latifundist.com, Top Lead. (201). 2016/2017 Ukrainian Agri Business Infographic. Retrieved from https://ukraineinvest.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/the-infographics-report-ukrainian-agribusiness-2017-eng.pdf, pg. 5.↩

3. Baker Tilly, Credit Agricole and AEQUO. “Agribusiness.” Your Investment Matters: Agribusiness. https://ukraineinvest.com. 2018. Web. 10 October 2018. ↩

4. Ibid.↩

5. Makarevych, Myroslava. “Olga Trofimtseva Talks about Future of Agriculture in Ukraine.” https://destinations.com.ua/business/trends-innovations/395-olga-trofimtseva-talks-about-future-of-agriculture-in-ukraine, UA Destinations, 31 May 2018. Web. 8 October 2018.↩

6. Baker Tilly, Credit Agricole and AEQUO. “Agribusiness.” Your Investment Matters: Agribusiness.↩

7. Ibid.↩

8. World Bank Group. August 2015. Shifting into Higher Gear: Recommendations for Improved Grain Logistics in Ukraine. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/451821468191333168/pdf/ACS15163-WP-P148859-PUBLIC-Box393203B.pdf.↩

9. Ibid.↩

10. Ibid.↩

11. Ibid.↩

12. Ministry of Economic Development and Trade of Ukraine. (2014). INVEST Ukraine Open for U. pg. 19↩

13. World Bank Group. August 2015. Shifting into Higher Gear: Recommendations for Improved Grain Logistics in Ukraine.↩

14. Baker Tilly, Credit Agricole and AEQUO. “Agribusiness.” Your Investment Matters: Agribusiness↩

15. Banga, Bhavya. “Global Precision Agriculture Market Anticipated to Reach $10.55 billion by 2025.” https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/global-precision-agriculture-market-anticipated-to-reach-10-55-billion-by-2025-bis-research-report-1027473195, Markets Insider, 21 August 2018. Web. 14 October 2018.↩

16. Gaidai, Nick. “Hot Investment: Agribusiness in Ukraine?” http://whartonmagazine.com/blogs/hot-investment-agribusiness-in-ukraine/#sthash.sFhG83nv.InVF7Hxr.dpbs, Wharton Blog Network, 21 May 2018. Web. 11 October 2018.↩

17. Krasnikov, Denys. “How technology is changing Ukrainian agriculture for the better.” https://www.kyivpost.com/technology/how-technology-is-changing-ukrainian-agriculture-for-better.html?cn-reloaded=1, Kyiv Post, 28 June 2018. Web. 15 October 2018.↩

18. Belenkov, Artem. “Artem Belenkov about Ukrainian Agricultural Holdings.” https://smartfarming.ua/en-blog/rozvitok-agtech-v-ukraini-skladno-ale-mozhlivo, SmartFarming, 11 July 2018. Web. 15 October 2018.↩

19. [Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations]. (16 October 2016). The future of agriculture in Ukraine. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fSQrAasTHNo. ↩

20. Gomez, James M & Choursina, Kateryna. “Ukraine’s Ban on Selling Farmland Is Choking the Economy: Kiev keeps putting off land reforms, despite pressure from the IMF and investors.” https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2018-01-02/ukraine-s-ban-on-selling-farmland-is-choking-the-economy. Bloomberg Businessweek, 1 January 2018. Web. 11 October 2018.↩

21. Ibid.↩

22. Transparency International. “Ukraine Takes Important First Step Towards Ending Corporate Secrecy.” https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/ukraine_takes_important_first_step_towards_ending_corporate_secrecy, Transparency International, 1 June 2017. Web. 17 October 2018. ↩

23. Makarevych, Myroslava. “Olga Trofimtseva Talks about Future of Agriculture in Ukraine.” 31 May 2018. Web. 16 October 2018↩

24. UkrAgroConsult. “Amounts of investment in Ukraine’s agricultural sector.” http://www.blackseagrain.net/novosti/on-investment-in-ukraine2019s-agriculture, UkrAgroConsult, 24 May 2017. Web. 9 October 2018.↩

Let GAI News inform your engagement in the agriculture sector.

GAI News provides crucial and timely news and insight to help you stay ahead of critical agricultural trends through free delivery of two weekly newsletters, Ag Investing Weekly and AgTech Intel.